- Home

- Photography Tours

- Diary / Blog

- Galleries

- Foreign Trips

- Tasmania 2016

- NE Queensland 2016

- Western Alps 2016

- NE Spain 2016

- Australia's Wet Tropics 2015

- Australia's Top End 2015

- SW Australia 2015

- Switzerland 2015

- Andalucia 2015

- Belize 2015

- Australia 2014

- Switzerland 2014

- Belize 2014

- Bahama Islands 2014

- Switzerland 2013

- Ecuador 2012-2013

- Florida 2011-2012

- Vancouver Island 2011

- Australia 2010

- Peru 2008

- Bulgaria 2007

- Lesvos 2006

- California 2006

- New Zealand 2005

- Extremadura 2005

- Goa, India 2004

- The Gambia 2003

- About

Switzerland

June/July 2015

Part 2

: Late-June Butterflies of Valais & Graubunden

Adonis Blue (Polyommatus bellargus)

Butterflies were my main focus for the latter part of the month and with around 100 species on the wing in Switzerland in late June there were plenty of subjects to chose from.

Large Ringlet (Erebia euryale)

Butterflies can often be incredibly frustrating things to photograph. First, if the weather is against you, finding them can be extremely difficult. Even if you can find them on the cold and cloudy days, the chances are that it will be hiding in deep cover with numerous grass stems or leaves getting in the way. Thankfully, I only had a couple of days of cloudy weather this year so at least that wasn't too much of a problem on this occasion.

Idas Blue (Plebejus idas)

Second, if the weather is hot (most of the days in late June were over 30°C this year) the butterflies can be hyper-active. Some species rarely settle when the weather is hot and sunny, spending all of their time fluttering around either searching for a mate, foodplants to lay their eggs on, or just defending their territories. This is particularly true for the larger butterflies, such as Purple Emperor, Apollo, and many of the Fritillaries.

Adonis Blue (Polyommatus bellargus) |

Due to the cold-blooded nature of insects, hot weather means the butterfly's metabolism is working at a higher, more optimal temperature, improving their reactions and responses to stimuli. In cooler weather, the butterfly may be more reluctant, or less able, to take flight at any perceived danger (such as a wildlife photographer sneaking in for a close-up), but when it gets warmer the butterflies often take flight much more readily and it can be extremely difficult getting close enough for the photo you want. I lost count of the times I spent half an hour or more carefully stalking a butterfly only for it to fly before I could get into position for a good photo.

Woodland Grayling (Hipparchia fagi)

The various species of Grayling can be particularly frustrating as these insects are so wary that even with a very slow and careful approach it is difficult to get within a couple of metres of them, never mind close enough for a frame-filling portrait!

Large Grizzled Skipper (Pyrgus alveus)

Unfortunately, just getting close enough for the butterfly to occupy a decent percentage of the frame does not guarantee you get a good photo. Thinking about the background is an extremely important consideration. Ideally, you want the butterfly to be perched on an isolated stem or flower with no other objects close behind so that the short depth of focus will throw everything behind the butterfly out of focus. If everything in the background is more or less uniform in colour, then you will get a nice uniform background with no distracting elements taking attention away from the main subject of your photograph. In the clutter of a real world meadow this is not an easy objective to achieve!

Small Blue (Cupido minimus) |

Idas Blue (Plebejus idas) |

In situations where there is a lot of close background clutter, such as in the photo below, it may sometimes be possible to reduce some of the distracting effect of it by keeping the lens aperture as wide possible (small f number). This will help to at least partially blur the background elements by reducing the depth of field.

Small Blue (Cupido minimus)

When using low f numbers the depth of field will usually be too narrow for the whole insect to be in sharp focus, and in these cases it is important to make sure the focus point is centered on the head. You can get away with the wingtips being out-of-focus but the photo will be ruined if the head is not sharp.

Amanda's Blue (Polyommatus amandus)

Amanda's Blue (Polyommatus amandus)

With many of the over 50 species of Lycaenids that occur in Switzerland being very similar to each other, identification of the "blues" can be difficult but, as with all things, familiarity with the common species, such as the Silver-studded Blue below, makes it much easier to spot unusual individuals among the crowd.

Silver-studded Blue (Plebejus argus)

Northern Brown Argus (Aricia artaxerxes)

Spotted Fritillary (Melitaea didyma)

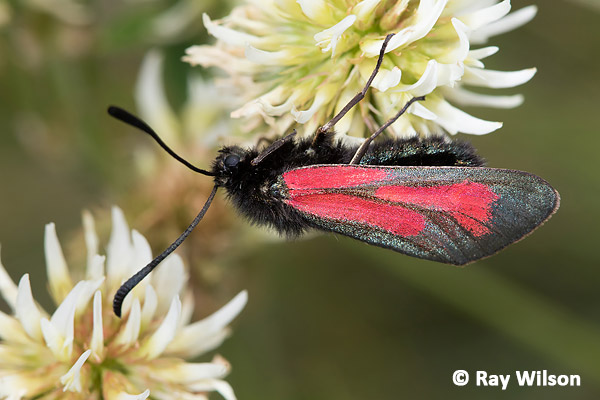

Transparent Burnet is one of several day-flying moths that are also commonly encountered in the alpine meadows.

Transparent Burnet (Zygaena purpuralis)

Ray Wilson owns the copyright of all images on this site.

They may not be used or copied in any form without prior written permission.

raywilsonphotography@googlemail.com